You’re familiar with the story… Across North America, the majority of infrastructure laid in the mid-20th century is quickly approaching – or has already reached – the end of its useful service life. According to the American Water Works Association, this has resulted in an estimated $1 trillion required to maintain and expand service to meet demands over the next 25 years (AWWA, 2017).

Within the United States, most of this deficit is borne by small water systems (serving fewer than 10,000 people) and very small water systems (serving fewer than 500 people) (US EPA, 2019). These small communities make up 97% of the more than 140,000 public water systems across the country. And while many of these systems consistently provide safe and reliable drinking water, it is almost always despite limited staffing and financial resources, sometimes even relying on volunteers.

Studies have also shown that the longer a municipality waits to invest in its infrastructure, the more costly upgrades or replacements become (AWE, 2014). So, as the manager of a small or very small water system facing these layers of adversity – how should you plan to address aging infrastructure and maintain safe, reliable water service delivery? And can you afford not to?

And after spending years helping small water system managers get a better handle on asset replacement, we have learned the importance of just getting started and adopting a long-term view. Many water system managers are aware of their capital needs over the next 1-5 years, but, among small systems especially, there is a lack of knowledge of long-term needs (say, over the next 25-100-years). Being aware and prepared for your long-term capital needs is part of being a prudent steward of your water system and it is essential to financial sustainability. But don’t let perfection (an expensive engineering firm’s asset management plan) be the enemy of the good (awareness of your long-term capital needs).

And after spending years helping small water system managers get a better handle on asset replacement, we have learned the importance of just getting started and adopting a long-term view. Many water system managers are aware of their capital needs over the next 1-5 years, but, among small systems especially, there is a lack of knowledge of long-term needs (say, over the next 25-100-years). Being aware and prepared for your long-term capital needs is part of being a prudent steward of your water system and it is essential to financial sustainability. But don’t let perfection (an expensive engineering firm’s asset management plan) be the enemy of the good (awareness of your long-term capital needs).

To help you with that, a significant amount of free resources are available to small water system mangers through the US Environmental Protection Agency, your state level Rural Water Association, the American Water Works Association, and UNC Environmental Finance Center. Also, a shameless plug: Waterworth is specifically designed for small water system managers who don’t have access to the same resources as larger centers; our smallest users have under 200 connections. We’re eager to help you get started on becoming financially sustainable and taking control of your water system. You can contact us here.

Beyond those resources, here are our 4 simple steps to getting started on building a long-term asset replacement plan.

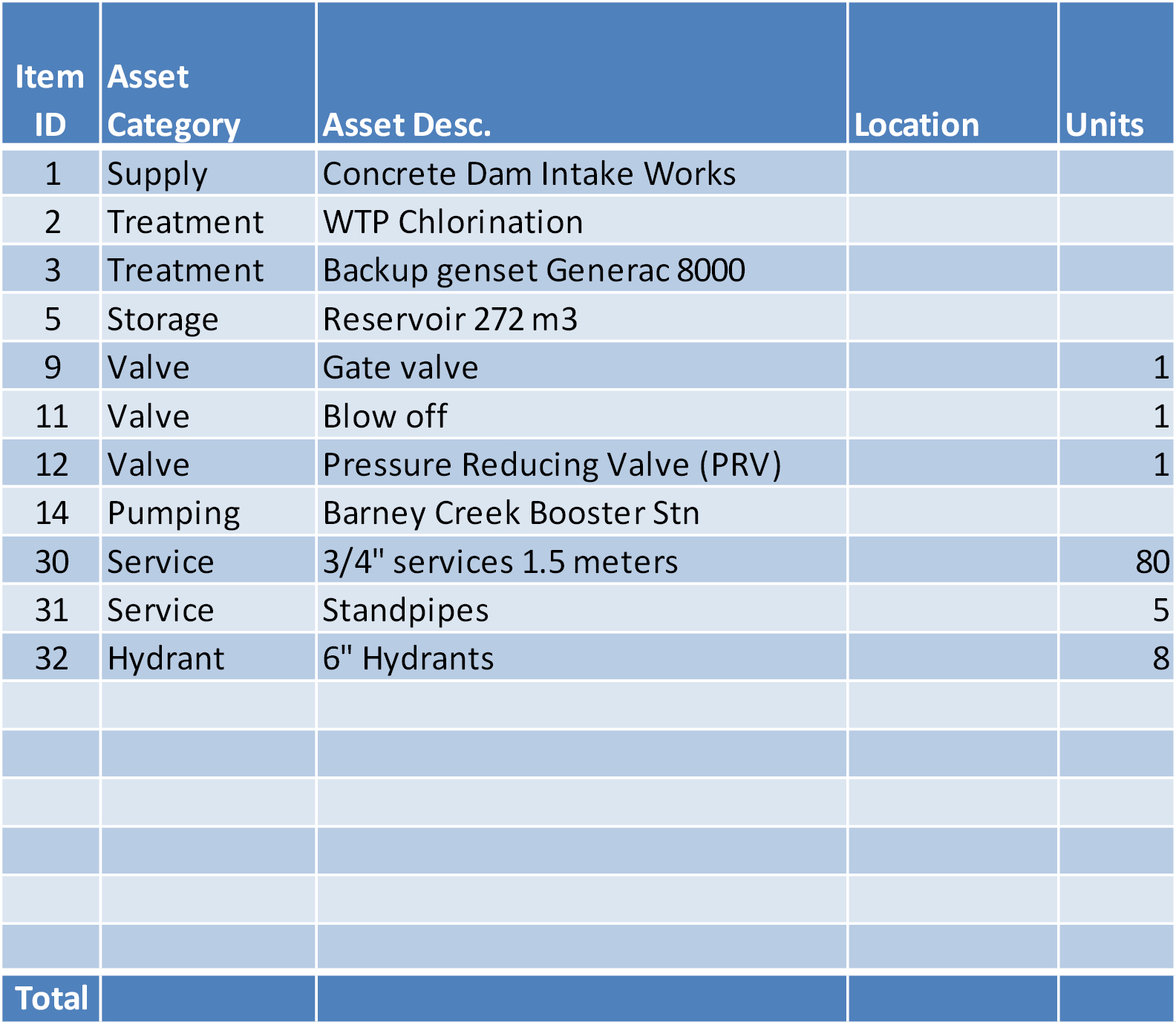

1. Inventory your system

Compile a list of all linear assets (water mains, transmission lines) and non-linear assets (pump stations, water treatment plants) in your system. Then, categorize these assets by type, such as “treatment” or “distribution”. Also include details such as location, quantity, size and material (if you can gather them).

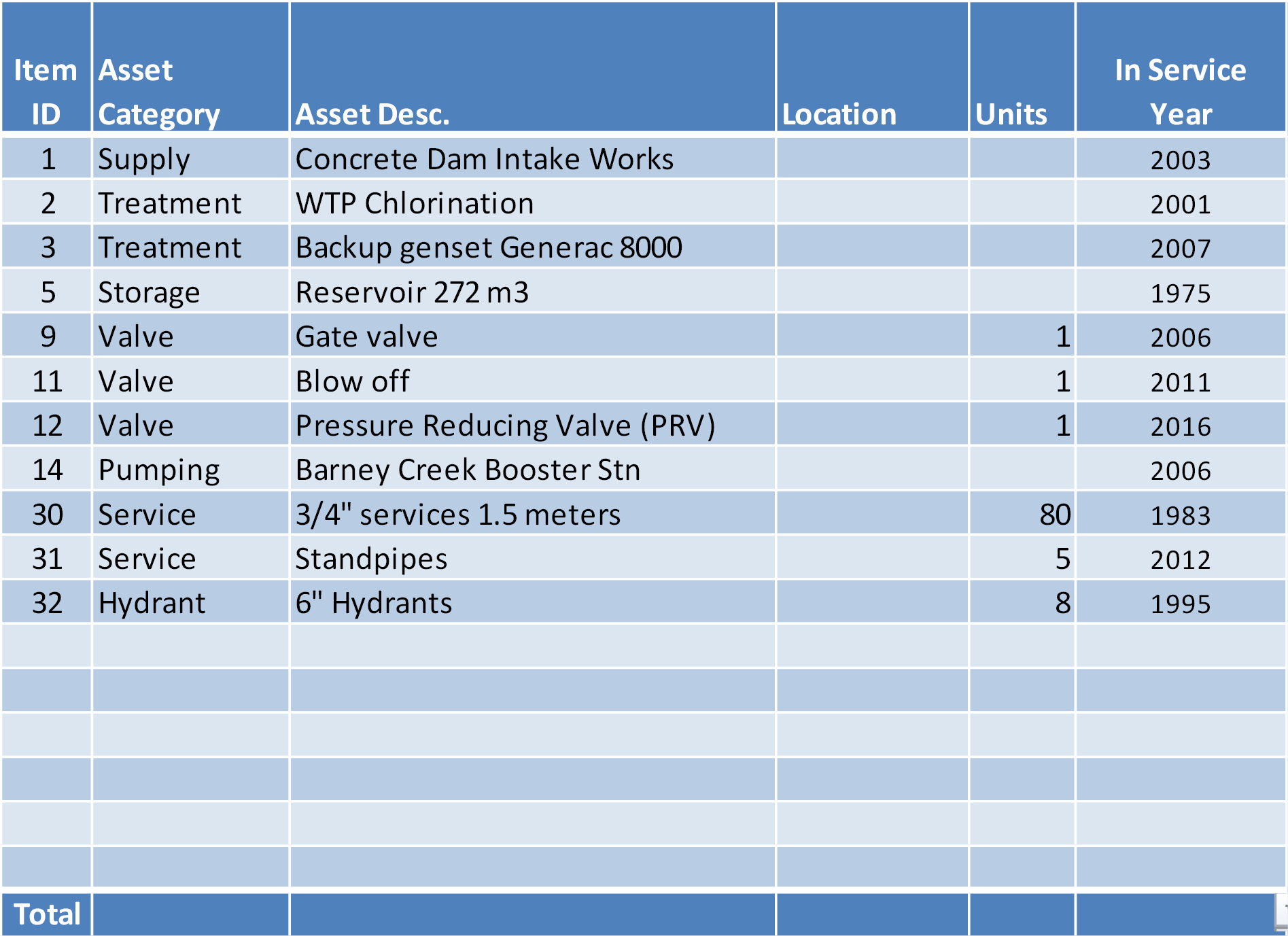

2. Determine the age of your assets.

Beside each asset, add the year that asset was put into service. You can look to old engineer’s diagrams for this information; however, an estimate is fine if you don’t have accurate records. If you have no idea, you can perhaps get creative and seek out former or long-term municipal employees or board/council members who might have some recollection.

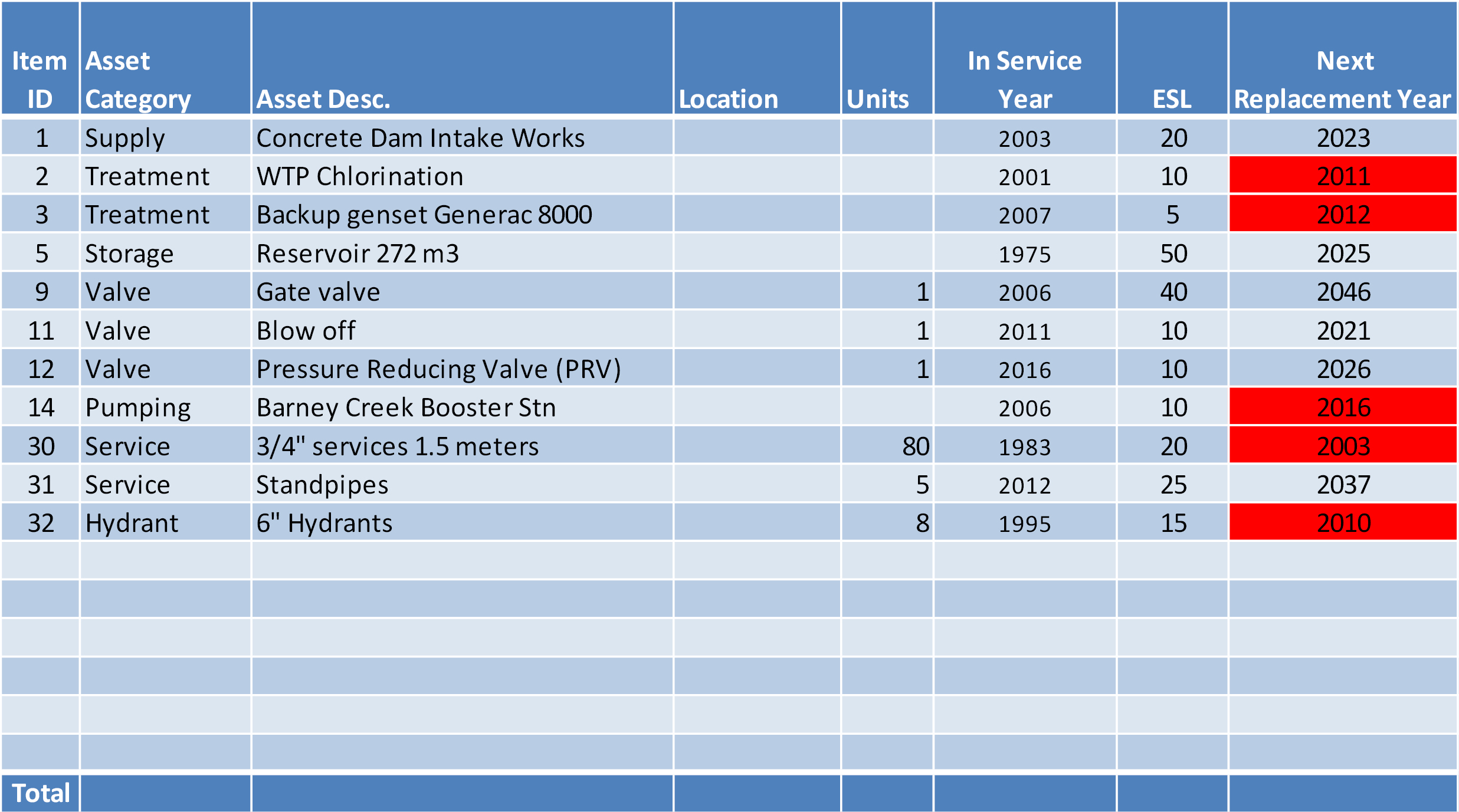

3. Estimate the service life of each asset

You may already have this knowledge, but there are also several resources you can turn to for industry standards. For example, you may already work with engineer who can help you, the EPA provides guidelines here, and Waterworth can also help you with this task (check out Funding Infrastructure Renewal for the Long Term).

Once you have added the estimated service life to the date that the asset was put into service, you will be able to determine the asset’s next replacement year. You may find that many of your assets are already well past this point – that’s okay. Now that you’re aware of the issues, you can start planning to address them.

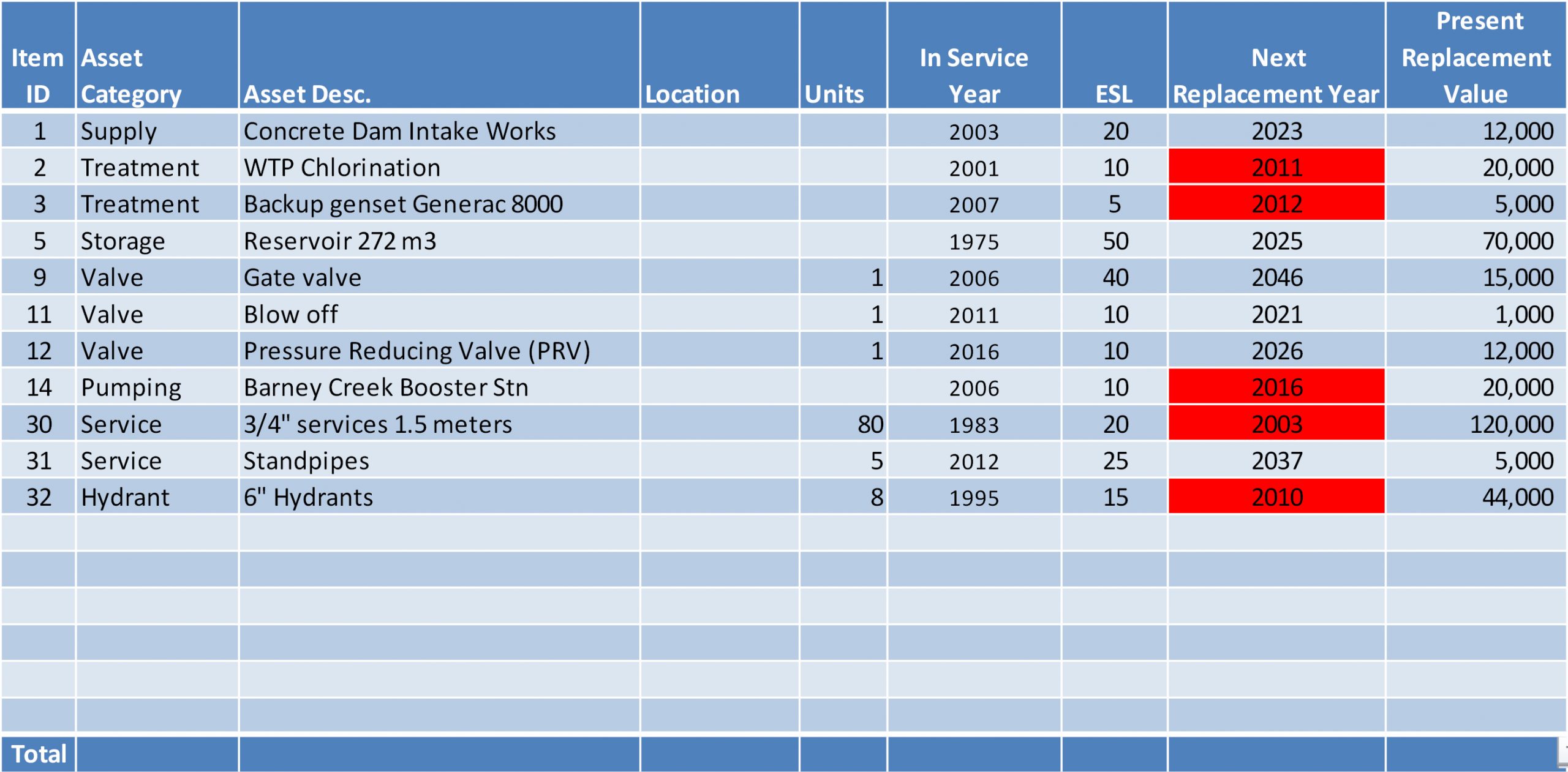

4. Estimate cost of replacement

This will depend on factors unique to your system, including geographic challenges and regional prices. But again, an estimate will do to just get started. Any engineering firm or Waterworth would be happy to help you with this work as well.

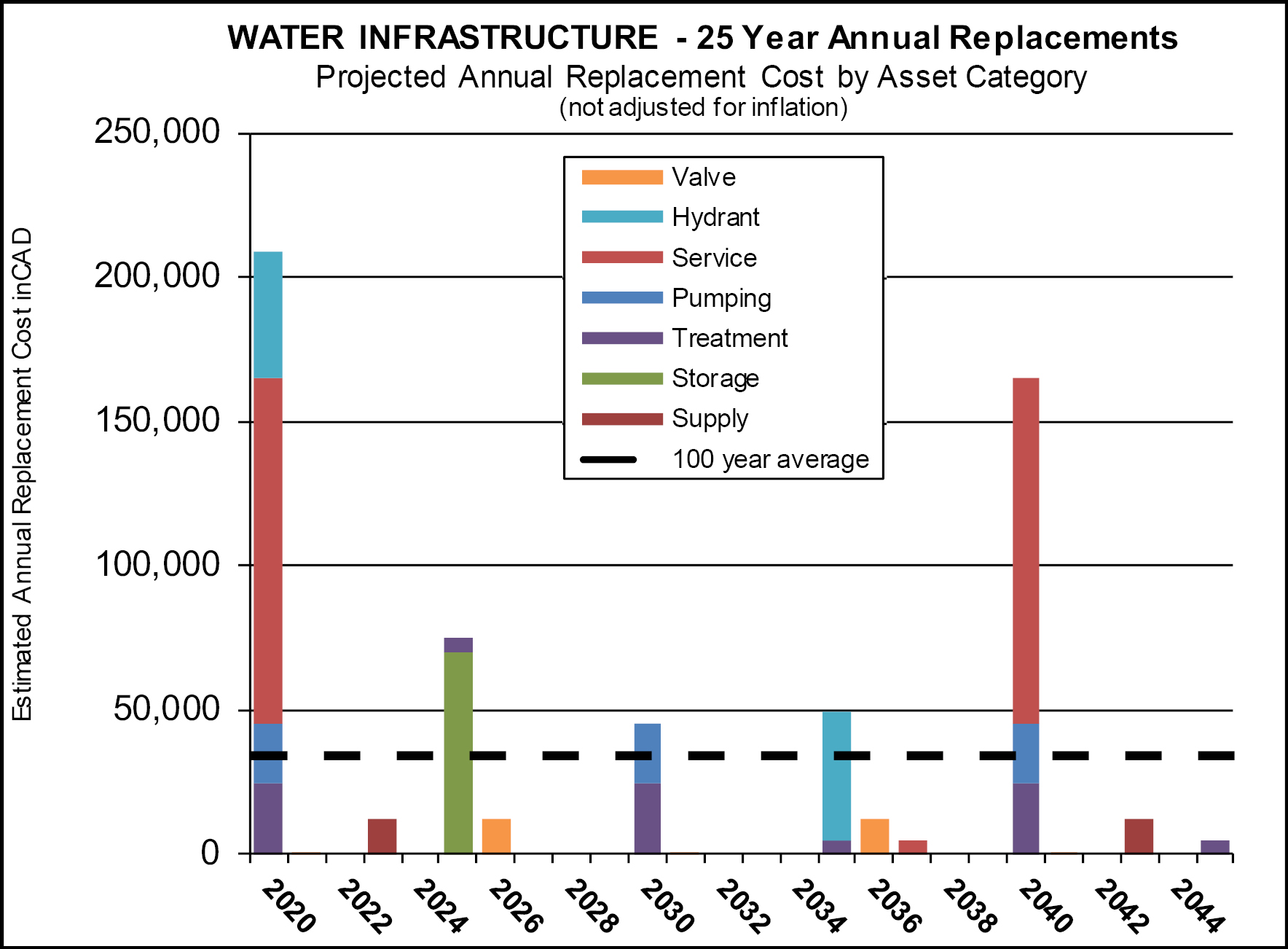

Once you have completed the steps above, you will be able to display that data in a graph such as this:

As you can see, there is already a backlog of work to be done (year 2020). If this is not attended to, each year the planned expenditures represented by the first bar will stack onto the work scheduled for the following year, and so on. To address asset replacement incrementally, you can also calculate the 100-year average of the cost of these replacements. That is, how much your utility should expect to need annually to keep up with asset wear. For more on this, including costs of borrowing and inflation, how to incorporate depreciation, and how to calculate your capital reinvestment rate, see Funding Infrastructure Renewal for the Long Term.

If your own graph looks a little hairy, don’t fret. By completing this exercise, you are already on the path towards financial sustainability. This graph is also useful to plainly communicate your utility’s needs to board/council members, shifting the conversation to proactive, long-term planning, rather than expensive, reactive repairs. There may be some catching up to do from previous years, in the form of rate increases, but awareness of your system’s present condition and future needs will allow you to ensure your utility continues to serve your community safely and reliably, well beyond your tenure.

Leave a Reply